This draft code forms part of the defined benefit funding code consultation.

You can save the contents of this page as a PDF using your web browser. Open the print options and make sure the destination/printer is set as 'Save as PDF':

The funding regime

Chapter 1 – Codes of Practice

Introduction

- This code of practice is issued by The Pensions Regulator (TPR), the body that regulates occupational pension schemes in the UK.

- Publication of this code of practice is a statutory requirement. It provides practical guidance on how to comply with the scheme funding set out in:

- Primary legislation – Part 3 of the Pensions Act 2004

- Secondary legislation:

- Occupation Pension Schemes (Scheme Funding) Regulations 2005

- Occupation Pension Schemes (Funding and Investment Strategy and Amendment) Regulations 2023

- This code applies to valuations with an effective date on or after [TBC].

- The code does not cover all aspects of pensions legislation. Trustees will be expected to seek the help of advisers and look beyond this code to help them understand all their legal obligations.

- The code is for trust-based occupational pension schemes providing defined benefits and is primarily for the scheme trustees and the scheme’s sponsoring employer. Certain aspects will apply to actuaries and other professional advisers will also find it of interest, including covenant and investment advisers.

Status of codes of practice

- Codes of practice are not statements of the law and failure to comply with the code does not of itself make a person liable to legal proceedings. However, legislation has delegated various matters to the code, which may (indirectly) be relevant to determining whether legal requirements have been met.

- When determining whether relevant legal requirements have been met, a court or tribunal must take any relevant provisions of this code of practice into account.

- In some scenarios there may be grounds for the regulator to pursue further action in the event of non-compliance with the requirements of Part 3 of the Pensions Act 2004. We may issue a s13 improvement notice, directing a person to take, or refrain from taking, such steps as are specified in the notice, or a s10 penalty notice. We may also use our s231 power to:

- modify future accrual;

- direct trustees to revise the scheme’s funding and investment strategy, the method and assumptions to be used in calculating the scheme’s technical provisions and/or the recovery plan, and/or

- impose a schedule of contributions

- These directions may be worded by reference to a code of practice issued by us.

Terms used in this code

- This code of practice sets out our interpretation of how to comply with relevant legislative requirements. Trustees may choose to follow an alternative approach to that appearing in this code of practice, provided they are satisfied that underlying legal requirements are met.

- In this code we use the word ‘must’ when referencing legal duties.

- Where we use the word ‘should’ or ‘expect’, or refer to our expectations, this indicates our view of good practice, rather than an express legal duty.

- We use ‘need’ where the process is necessary to allow a scheme to operate even though there is no expectation or legal requirement in place.

Related guidance

- We will make clear on our website which code-related guidance derives from this code.

Chapter 2 – An outline of the funding regime

- The scheme funding regime comprises two separate, but interlinked, requirements:

- To plan for the long-term funding of the scheme.

- To carry out valuations showing the current funding position of the scheme.

- This section summarises these requirements. Further details are set out in the rest of this draft code.

Long-term planning

- The Funding and Investment Strategy Regulations require trustees to carry out these steps in planning for the long-term funding of the scheme:

- To determine a funding and investment strategy, dealing with:

- the planned funding ‘end game’ over the long-term

- the journey plan, bridging from the current funding position to that ‘end game’.

- To record the above, and further supplementary matters, in a statement of strategy.

- To determine a funding and investment strategy, dealing with:

Funding and investment strategy

- For the purposes of determining their ‘end game’, trustees must determine:

- how they intend the scheme to provide benefits in the long-term (their long-term objective or 'LTO')

- the funding level they intend the scheme to have reached, and the investments they intend to hold, at a particular date (the relevant date).

- The funding level the trustees intend the scheme to have reached must be calculated on the low dependency funding basis.

- Trustees must obtain the employer’s agreement to the funding and investment strategy.

The LTO

- Benefits can be provided by schemes in a number of ways, including:

- running off the scheme, paying the benefits from the scheme as they fall due

- buying out members’ benefits with an insurer

- transferring the scheme assets and liabilities to a DB superfund or another consolidation vehicle

- The chosen strategy should be taken into account when considering the other elements of the funding and investment strategy, for example if the strategy is to buy out benefits, the trustees may adopt a higher funding target at the relevant date.

- For open schemes, trustees need to consider how they would provide accrued benefits for existing members over the long term, as set out above. However, we recognise that, if trustees assume that membership will remain stable over time, the scheme may not get closer to its relevant date in practice.

The relevant date

- A scheme’s relevant date is set by the trustees. It must not be later than the end of the scheme year in which the scheme is expected to reach (or did reach) significant maturity (though it can be any date in advance of this deadline).

- The scheme actuary is responsible for estimating the date of significant maturity. This estimate must be produced by reference to the ‘duration’ of the scheme’s liabilities. Further detail is set out in Chapter 5.

- Where a scheme has not reached the relevant date, the actuary should also estimate the expected maturity of the scheme at that (future) date.

Investments after the Relevant Date

- For the purposes of the funding and investment strategy, trustees must assume that scheme assets will be invested in accordance with a low dependency investment allocation on and after the relevant date.

- A low dependency investment allocation is an investment strategy under which:

- the cash flow from the investments is broadly matched with the payments under the scheme, and

- the value of the assets relative to the value of the scheme’s liabilities is highly resilient to short-term adverse changes in market conditions

- Trustees must ensure that the risks in the assumed investment strategy are sufficiently prudent, so that no further contributions would be expected to be required from the employer if the scheme was fully funded (further detail in relation to this test is set out in Chapter 3).

- Trustees must also assume that scheme assets will be invested on and after the relevant date in investments with sufficient liquidity to enable the scheme to meet expected cash flow requirements and make reasonable allowance for unexpected cash flow requirements.

- Further details on how trustees should approach these requirements are set out in Chapter 3.

Low Dependency Funding Basis

- A scheme’s liabilities must be calculated in accordance with the low dependency funding basis for the purposes of the funding and investment strategy.

- A low dependency funding basis must use actuarial assumptions which are set such that if one was to presume that:

- the scheme was fully funded on that basis, and

- the scheme’s assets were invested in accordance with the Low Dependency Investment Allocation, then

no further employer contributions would be expected to be required.

- Further details on how trustees should approach these requirements are set out in Chapter 4.

The long-term funding target

- Trustees must determine the funding level they intend the scheme to have achieved as at the relevant date – the long-term funding target. This must be calculated by reference to the low dependency funding basis.

- The long-term funding target level must be at least 100% - ie as a minimum, the trustees’ target must aim to be fully funded on the low dependency funding basis. However, trustees may target a higher funding level, for example if their strategy is to buy out benefits.

Journey plan

- Trustees must plan how they intend the scheme to reach its long-term funding target. This is referred to as the journey plan.

- When determining the journey plan as part of the funding and investment strategy, trustees must consider how they intend to transition from their current investment strategy to a strategy which would meet the standards of a low dependency investment allocation.

- Trustees must ensure that this transition is:

- dependent on the strength of the employer covenant, where more risk can be taken if the covenant is strong

- subject to the above, dependent on the maturity of the scheme

- Trustees’ investment plans must be expected to provide sufficient liquidity to enable the scheme to meet expected cash flow requirements and make reasonable allowance for unexpected cash flow requirements.

Statement of strategy

- Trustees must prepare a written statement of strategy made up of two parts:

- Part 1, which records the funding and investment strategy

- Part 2, which records various supplementary matters (including matters related to the journey plan, how well the funding and investment strategy is being implemented, the main risks to the strategy and how they are being managed)

- The level of evidence and explanation required in the statement of strategy will depend on the complexity of the risk taken.

- Trustees must consult with the employer when preparing or revising Part 2 of the statement of strategy.

Determination, review and revision

- A scheme’s first funding and investment strategy must be determined within 15 months of the effective date of the first applicable actuarial valuation. The first applicable actuarial valuation is the first valuation with an effective date on or after [date].

- The funding and investment strategy must be reviewed and, if applicable, revised within 15 months of the effective date of each subsequent valuation (and in the other circumstances set out in Appendix 2).

- Trustees must record their first funding and investment strategy, in a statement of strategy, a copy of which must be sent to us with the relevant actuarial valuation.

- Whenever the funding and investment strategy is reviewed:

- if that review has led to a revision of the funding and investment strategy, Part 1 of the statement of strategy must be updated to reflect the revisions; and

- regardless of whether there has been any revision of the funding and investment strategy, Part 2 of the statement of strategy must be reviewed and, if applicable, revised.

- A scheme’s first statement of strategy must be sent to us with the first valuation after the regulations come into force. The statement of strategy must be reviewed and, if needed, revised after any review of the scheme’s funding and investment strategy, which must be at least as often as the scheme’s valuations.

- If the statement of strategy is revised as part of a corresponding valuation process, that revised statement must be sent to us. A statement of strategy that is revised between valuations does not need to be sent to us.

Valuations

- Every DB scheme is subject to the statutory funding objective, which is to have sufficient and appropriate assets to cover its technical provisions (TPs).

- Under Part 3 of the Pensions Act 2004, trustees must obtain actuarial valuations every year. However, trustees can choose to obtain valuations at up to triennial intervals, provided that they obtain an actuarial report for each intervening year.

- An actuarial valuation is a written report prepared and signed by the scheme actuary, valuing the scheme’s assets and calculating the scheme’s TPs on a specific date, known as the effective date.

- Where a valuation shows that a scheme did not meet the statutory funding objective on the effective date, a recovery plan must be put in place in order to return the scheme to full funding.

Interaction between the funding and investment strategy and valuations

- There is a close interrelation between actuarial valuations and the long-term planning requirements. These include the following:

- Each actuarial valuation must include the actuary’s estimate of the maturity of the scheme (calculated in accordance with the funding and investment strategy regulations) and the date on which the scheme will reach significant maturity.

- Each actuarial valuation must estimate the funding position of the scheme as at the effective date, calculated on the low dependency funding basis as determined in the funding and investment strategy.

- The assumptions used in the actuarial valuation must be consistent with the funding and investment strategy in the following ways:

- The valuation assumptions applicable to the period following the relevant date must be actuarially consistent with the low dependency funding basis assumptions as determined in the funding and investment strategy;

- The valuation assumptions applicable to the period preceding the relevant date must be calculated in a way that is consistent with the planned investment transition, as set out in the journey plan element of the funding and investment strategy.

- The relevant date used for the purposes of the funding and investment strategy depends on the actuary’s estimate of significant maturity, as set out in the corresponding actuarial valuation.

- Given this interaction, we expect trustees to consider the funding and investment strategy and valuation together as one. This is likely to be an iterative process as trustees’ understanding of their scheme and employer covenant develops, their plans evolve for managing the scheme risks, and ongoing dialogue with their employers develop. We expect trustees and employers to work collaboratively during this process (see Appendix 1).

- Trustees are not required to invest in accordance with the low dependency asset allocation determined as part of the funding and investment strategy. There may be good reasons not to do so, for example an employer refusing to agree to a strengthening of the LDIA that the trustees consider appropriate being recorded in the FIS or where a scheme has a material surplus after the relevant date. However, given that significantly mature schemes have less capacity to make good negative investment outcomes, in most cases we expect trustees to exercise their investment powers after the relevant date in a way that is consistent with the low dependency investment allocation.

- The following sections in this code set out our expectations for how trustees should approach these various elements and processes.

Long term planning

Chapter 3 - Low dependency investment allocation

- For the purposes of the funding and investment strategy, trustees must assume that on and from the relevant date scheme assets will be invested in accordance with two principles:

- The investments would meet the requirements of a low dependency investment allocation; and

- The assets would be sufficiently liquid to enable the scheme to meet expected cash flow requirements, and with reasonable allowance for unexpected cash flow requirements.

- A low dependency investment allocation is an investment strategy under which:

- the cash flows from the investments are broadly matched with the payments of benefits under the scheme, and

- the value of the assets relative to the value of the scheme’s liabilities is highly resilient to short-term adverse changes in market conditions.

- The assumed investment strategy must meet the requirements above with the result that, when considering the overall prudence of the scheme’s low dependency funding basis, no further employer contributions are expected to be required to meet the benefits under the scheme in respect of accrued rights. Further details of this test are set out in Low dependency funding basis chapter below.

Broad cash flow matching

- ‘Cash flow matching’ is an approach which allows schemes to hold assets whose expected cash flows to the scheme mirror those of the schemes expected benefit and expense payments. This gives the trustees confidence that the assets they hold will be able to pay the benefits and expenses as they fall due.

- Scheme investments can be classified as being either 'growth' or 'matching' assets. Assets that meet the below criteria can be considered to be matching assets:

- The income and capital payments are stable and predictable; and

- They provide either fixed cash flows or cash flows linked-to inflationary indices.

- The main asset classes that would meet these criteria include cash, government bonds and corporate bonds. Interest rate and inflation derivatives (including gilt repos) can also be deemed as matching where they provide payments to match the liabilities of the scheme. Illiquid and alternative credit including, for example, some property and infrastructure related investments, can also be used for matching purposes if they meet the criteria above.

- We would expect that matching assets would be heavily weighted towards investment grade bonds (or equivalent) but some sub-investment grade assets may usefully contribute to meet scheme outgo.

- As one of the requirements in the definition of 'low dependency investment allocation' is to be broadly cashflow matched with the payment of pensions and other benefits under the scheme, trustees should consider the expected payments from the scheme. In this regard it will be necessary for the Trustees to take advice from the scheme actuary regarding the expected cash flows and whether any adjustments are required to the funding assumptions for this purpose. For example, it may be necessary to take account of different levels of tax-free cash at retirement to reflect actual experience or whether allowance should be made for either early or late retirement patterns (which might be cost neutral for funding purposes). It is important that Trustees understand the risks from actual scheme outgo differing from expected scheme outgo and how changes in the key demographic assumptions impact on those expected cashflows.

- Trustees may choose to determine an investment portfolio for the purposes of their funding and investment strategy under which the scheme assets would match all future payments from the scheme. However, that level of cashflow matching is not required for the purposes of the low dependency investment allocation as the minimum requirement is only for broad cashflow matching. A scheme’s low dependency asset allocation can therefore contain a mix of 'growth' and 'matching' assets.

- Trustees may choose to determine an investment portfolio for the purposes of the low dependency investment allocation that only partially matches future liability cashflows, but plan to put in place alternative hedging strategies to manage their interest rate and inflation risks in relation to the portion of their future liability cash flows that are not matched.

- Future interest rates and inflation are not necessarily expected to remain the same. The yield curve describes the rate of interest that is obtainable (in real and nominal terms) over different time periods. If interest rates or inflation pricing changes, the shape of yield curves can change whilst at the same time the average interest rate or inflation assumption for the scheme might remain unchanged. Therefore, when determining the low dependency investment allocation, it is important to consider hedging against the shape of the interest rate yield curve or inflation yield curve rather than just the average duration of the liabilities only.

- It is acceptable for trustees to 'bucket' cash flows from the scheme by aggregating the expected cash flows of the scheme over, for example, short, medium and long durations (or by defined periods) in order to determine where the liabilities fall on the yield curve. This will enable trustees to plan for the purchase of matching assets and implement hedging strategies so that they are aligned with the duration of the liability cash flows.

- We therefore believe an approach where the scheme adopts a low dependency investment allocation which assumes some cash flow matching for a portion of their liabilities combined with high levels of hedging for interest rate and inflation consistent with the duration of their liabilities – including differing points along the yield curve – would be sufficient to be deemed broadly cash flow matched.

- We expect that, through the above approaches, and consistent with the broadly matched requirements, schemes should seek to have a minimum level of interest rate and inflation hedging of at least 90% for the purposes of their low dependency investment allocation.

- One example of meeting our expectation would be to have a low dependency investment allocation made up of the following asset classes:

- corporate bonds and government gilts: 85% (assuming appropriate maturities and durations for the bonds)

- growth assets: 15%

- When determining the low dependency investment allocation, trustees should also consider the requirements of high resilience to short-term adverse market changes and liquidity (as discussed below).

- The extent of the level of accuracy should be proportionate to the size of the scheme and governance arrangements. In addition, where the allocation of growth assets in the low dependency investment allocation is higher, more attention should be paid to the composition of the matching assets. The key variables that can be varied in the matching portfolio will be the quantum of leverage and increasing the duration of the matching assets relative to the liabilities. Further consideration of governance arrangements will also be needed given the liquidity risks associated with any leverage arrangements.

High resilience to short-term adverse changes in market conditions

- The investment strategy assumed for the purposes of the funding and investment strategy must also be such that the value of the assets relative to the value of the scheme’s liabilities is highly resilient to short-term adverse changes in market conditions.

- We expect trustees to carry out a suitable level of analysis to enable them to assess the resilience of their low dependency investment allocation to short-term adverse market changes. The complexity and sophistication of this analysis will depend on the individual circumstances of the scheme.

- Trustees must assess both the asset and liability side.

- As the low dependency investment allocation will contain matching assets to match payments from the scheme, changes in the short-term market value of these assets should not affect their ability to continue to meet the liability cash flows. In this scenario, it is expected that the movement in the value of the assets, and the consequential movement in the yield on those assets, will cause a similar movement in the value of the liabilities.

- Detrimental returns on growth assets would also reduce the level of assets in relation to the liabilities. Trustees should also be cognisant of the market and illiquidity risks of the growth assets and how this affects the riskiness of the investment strategy relative to the liabilities when considering the proportion of growth assets within any low dependency investment allocation portfolio.

- As a minimum, we expect schemes to test for a one-year, 1-in- 6 stress scenario when testing for resilience and, assuming they are fully funded on a low dependency funding basis, for the results of this test to be limited to a change in funding level of 4.5%. Beyond this level is likely to mean that the scheme is not sufficiently cash flow matched and/or the level of growth assets is such that the overall portfolio is not resilient to changes in short-term market conditions.

- Trustees should also assess how well the assets match the liabilities by looking at the sensitivity of the assets and liabilities at different maturity terms of the liabilities. This could be done by scenario testing, or more detailed analysis looking at changes in the overall shape of the yield curve to determine the impact of changes in both the value of assets and liabilities at different maturity terms.

- We would also expect trustees to consider other forms of analysis to understand the resilience of their low dependency investment allocation portfolio. For example, in relation to the cashflow matching assets, trustees should consider how the cashflows generated are likely to perform compared to the expected scheme outgo under a range of different stresses and scenarios.

- These scenarios could include consideration of alternative scenarios in relation to the matching assets for default rates (net of recovery), the impact of collateral calls for schemes using leverage and how the shape and level of the liability cashflows impacts the resilience. Trustees should discuss with the actuary when understanding cashflow projections the impacts of the key assumptions impacting those projections and the effects of prudence.

Liquidity

- When the trustees have identified a hypothetical portfolio which meets the cashflow and resilience criteria, they should consider whether the investments would provide sufficient liquidity.

- We do not expect a detailed assessment of liquidity for the purposes of setting the low dependency investment allocation. Instead, trustees should consider the general characteristics of the asset classes.

- More detailed consideration in relation to liquidity for the assets schemes hold is set out in the Liquidity section in the Application section of this code.

Proportionality

- We expect schemes to take a proportionate approach in setting their low dependency investment allocation strategy in line with the above expectations.

- We expect a greater focus on the granularity of the approach to matching and the risks associated with their low dependency asset allocation as a scheme approaches their relevant date.

- For a scheme of average maturity, it would be reasonable to articulate their low dependency investment allocation in terms of expected return, broad asset allocation and level of interest rate and inflation hedging. As a scheme approaches its relevant date, we would expect the level of detail for the low dependency investment allocation to increase.

- This is because, for the purposes of setting the funding and investment strategy, trustees must follow the principle that scheme assets are invested in accordance with the low dependency investment allocation on and after the relevant date. As set out in the section on 'investment and risk management considerations', when it comes to the way the scheme actually invests, our expectation is that investment decisions by trustees (and fund managers to whom decision making has been delegated) will generally be consistent with the strategies set out in the funding and investment strategy (which, after the relevant date, means the low dependency investment allocation).

Chapter 4 - Low dependency funding basis

Introduction

- A low dependency funding basis must use actuarial assumptions that are set so that if:

- the scheme was already funded on a low dependency basis, and

- the scheme’s assets were invested in accordance with the low dependency investment allocation, then

- Trustees should assess whether the low dependency test would be met under most reasonably foreseeable scenarios.

Setting individual assumptions

- We do not expect trustees to have to stochastically model each assumption or set of assumptions to satisfy themselves that the low dependency test has been met.

- Trustees should ensure that the assumptions are chosen prudently and understand the risk in the funding basis so that they can be satisfied that further contributions are not expected to be required.

- Assumptions should refer to statistically credible data where relevant. This is data considered to be accurate, complete and large enough that it can reasonably be used to estimate future experience with a high degree of confidence. Consideration should be given to the time period the data is collected over, noting that they should be drawn from a time period expected to give a good guide to future experience. We would generally expect this to be the most recent data available but ignoring any time period where the data collected may be considered anomalous.

- We recognise that trustees may choose to include a high level of prudence in some assumptions, while others are closer to a best estimate approach.

- Some assumptions may also be more uncertain and have a greater effect on the measurement of liabilities than others. As such, trustees should pay closer attention to the prudence included in these assumptions and ensure it is sufficient for them to be confident it would not undermine the low dependency test.

- Appendix 3 sets out how we expect trustees to approach the main individual assumptions (excluding the discount rate, which is set out below).

- The table in appendix 3 sets out our expectations on expenses for use in the low dependency funding basis, depending on what the scheme rules require about the employer to pay expenses, the maturity of the scheme, and whether the scheme is at/past the relevant date.

The low dependency discount rate

Approach to setting the discount rate

- The main approaches we expect trustees to take when setting the low dependency discount rate are as follows:

Risk-free rate + approach

- Under this method, the discount rate could be expressed allowing for a margin over a risk-free yield.

- An acceptable risk-free yield includes:

- the gilt yield, or

- the yield on swaps if adjusted for the probability of default

- The margin added to the risk-free rate should be a prudent estimate of the return on the trustees’ low dependency investment allocation.

Dynamic discount rate approach

- Where a scheme has purchased cash flow matching assets that meet the expectations in this code, the discount rate can be based on the return of those assets adjusted to allow for a prudent level of default and downgrade informed and evidenced by historical data to give a return.

A combination of both approaches

- Trustees may choose to use a combination of the two methods. For example, they may use the risk-free rate + approach for parts of the portfolio with longer durations and the dynamic discount rate where, post relevant date, assets match the cash flows. As and when further matching assets are bought and become appropriate, the associated liabilities can be moved to the dynamic discount rate approach.

Use of gilt yield curve for the discount rate

- Consistent with our expectations for TPs, our general expectation is that yield curves should be used.

Chapter 5 - Relevant date and significant maturity

Introduction

- The funding and investment strategy must set out the trustees’ long term objective and the funding level they intend the scheme to have reached, and the investments they intend to hold, at the relevant date.

- A scheme’s relevant date is set by the trustees. It must not be later than the end of the scheme year in which the scheme is expected to reach (or did reach) significant maturity (though it can be any date in advance of this deadline).

- The scheme actuary is responsible for estimating the date of significant maturity. This estimate must be produced by reference to the ‘duration’ of the scheme’s liabilities, calculated on the scheme’s low dependency funding basis. A scheme reaches significant maturity when it reaches the duration of its liabilities (measured in years) specified in this code. The specified duration can be found below.

- A scheme’s year may be modified in certain circumstances. However, for the purpose of setting the relevant date, trustees should assume that the current scheme year end will continue unamended.

Calculating current and projected duration (maturity)

- Payments in respect of pensions and other benefits will be made from a scheme at different points in time and those payments will have different values. Duration is the weighted mean time until those payments are expected to be made weighted by the discounted value of those payments. Duration is measured in years.

- The scheme actuary should calculate the current and projected duration of the scheme. When calculating duration, the payments expected to be made from the scheme should be estimated using the scheme’s low dependency funding basis.

- In most cases, we expect trustees to calculate duration using the following formula for the Macaulay duration (though for smaller schemes, trustees may choose to adopt a simplified approach so long as the output is duration of liabilities measured in years):

∑i ticfivi ∕ ∑i cfivi

Where;

cfi is the ith projected cashflow

ti is the (average) time that cfi is expected to be paid

vi is the discount factor appropriate at time i

The denominator in the equation is the value of the low dependency liabilities.

The calculation can be rounded to one decimal place.

Cashflows can be aggregated into those expected over a period of a year or less.

Significant maturity

- For the purposes of regulation 4(1)(b) of the funding and investment strategy regulations, the duration at which a scheme reaches significant maturity is 12 years.

- The estimate of the date on which the scheme is expected to (or, if applicable, did) reach significant maturity must be reviewed on each occasion the funding and investment strategy is reviewed.

- However, where a previously determined relevant date has passed, and the trustees have no reason to believe that the date of significant maturity has materially changed, trustees may choose to instruct the scheme actuary to carry out a broad approximate estimate of the date of significant maturity. In these circumstances, we would not expect any detailed calculations to be carried out to determine this date.

Relevant date

- Trustees must determine their relevant date, which cannot be later than the end of the scheme year in which the scheme reaches significant maturity.

- When setting the relevant date, trustees should assume that the scheme year will remain as it is at the time the funding and investment strategy is being set or revised (as appropriate).

- Where a scheme has not reached the relevant date, the scheme actuary must estimate the expected maturity of the scheme at that date. If the trustees consider it convenient, the actuary may use the maturity as at any date within the scheme year in which the relevant date will fall, as being representative of the maturity as at the relevant date.

Chapter 6 - Employer covenant

Introduction

- A scheme’s journey plan is their planned progress in accordance with its funding and investment strategy as it moves towards the relevant date.

- In order to assess what journey plan would be appropriate, trustees must bear in mind the strength of the employer covenant. In particular, that the investment de-risking journey should be:

- dependent on the strength of the employer covenant, where more risk can be taken if the covenant is strong

- subject to the above, dependent on the maturity of the scheme

- This section sets out how we expect trustees to assess the strength of the employer covenant. This assessment should be proportionate to the specific circumstances of the scheme and employer. The journey planning section gives more details of this proportionality.

Covenant assessment

- The strength of the employer covenant is determined by:

- the financial ability of the employer to support the scheme

- scheme support from any contingent assets to the extent these:

- are legally enforceable, and

- will be sufficient to provide that level of support when required

- Trustees must consider the following matters when assessing the employer’s financial ability to support the scheme:

- The employer’s cash flow.

- The likelihood of an employer insolvency event[1] occurring.

- Other factors that are likely to affect the performance and development of the employer(s) business.

- The nature of the trustee’s assessment will depend on the circumstances of the scheme and employer. We would expect the strength of the employer covenant to be considered relative to the scheme’s:

- low dependency deficit, and

- solvency deficit

- For employers where insolvency is highly unlikely over the short to medium term, their strength relative to the low dependency deficit will help the trustees understand the support available for their journey plan. The higher the risk of insolvency, which would trigger a debt due under section 75 of the Pensions Act 1995, the more weight there should be on employer support relative to the solvency deficit.

General principles and expectations

- Trustees are required to carry out an employer covenant assessment to understand the extent to which the employer can support the scheme now and in the future. In general, trustees should focus on the ability of the employer to make cash contributions to the scheme to address downside investment risk. Contingent assets can also be valuable where the trustees can evidence that the contingent asset is legally enforceable, will be sufficient to provide the level of support when required, for example where a guarantor is substantially stronger than the employer and provides an all monies guarantee.

- We expect trustees of all DB schemes to assess covenant support. However, the required depth and frequency of an assessment should be proportionate to the circumstances of the scheme and employer. The approach taken should be documented and trustees should be able to justify why it is reasonable and appropriate.

- The covenant should be assessed in the context of, and relative to, the scheme’s funding and investment risk. Trustees should consider the following:

- The size of the scheme’s low dependency liabilities relative to the strength of covenant support.

- The level of investment and funding risk, providing an indication of how the scheme’s funding requirements and reliance on covenant support could change over time with changes in market and financial conditions.

- The maturity and the expected cash flows of the scheme, as this will affect the timing of the scheme’s reliance on the covenant.

- We expect employers (and, where relevant, third parties that have provided contingent assets) to provide trustees with the information required to assess covenant. If appropriate information is not provided, trustees are unlikely to be able to demonstrate how the covenant can support the risks the scheme is taking. Consequently, where appropriate, trustees should consider reducing their reliance on covenant when setting investment and funding strategies in their funding and investment strategy.

The financial ability of an employer to support the scheme

- The financial ability of an employer to support the scheme derives from the following:

- The employer’s cash flow, as set out in this code.

- Other factors that are likely to affect the performance and development of the employer(s) business, including the likelihood of an employer insolvency event occurring, as set out in this code (the employer’s prospects).

- An assessment of the employer’s financial ability to support the scheme is primarily forward-looking and should consider the following:

- Visibility over employer’s forecasts. This typically covers a period of between one to three years. In addition to considering the forecast cash flows, trustees will need to consider profit and loss account and balance sheet forecasts to understand the short-term prospects of an employer. When assessing the reasonableness of employer forecasts, trustees should consider the historical accuracy of managements forecasts as well as the appropriateness of the assumptions underpinning these forecasts.

- Reliability over available cash. This represents the period where trustees have reasonable certainty over the employer’s available cash to fund the scheme. When assessing reliability, trustees should consider the employer’s forecasts, to the extent that these are available and deemed reasonable, and the employer’s prospects (including its capital structure and overall resilience, and the market in which it operates). Most employers will only have reliable periods over the medium term. However, some employers’ reliable period may extend to the long term.

- Longevity of the covenant. This represents the maximum period in which trustees can reasonably assume that the employer will remain in existence to support the scheme.

Identifying employers

- Trustees should identify which entities are employers for the purposes of Part 3 of the Pensions Act 2004.

- Entities that are not employers for these purposes should not be taken into account directly when considering this element of covenant. However, where the employer’s financial performance is heavily dependent on a third-party or group obligation (for example under a cost-sharing agreement), or the overall performance of the wider group, trustees should consider the implications of this when assessing an employer’s cash flow forecasts and prospects.

- If a group entity or other third-party provides contractually binding support directly to the scheme, this may amount to a contingent asset and should be considered as set out in the 'Contingent assets' section below.

Assessing cash flow

- An employer’s cash flow means the free cash flow generated by the employer after taking account of reasonable operational costs (for example utility costs, essential maintenance, staff costs), but before deficit repair contributions (DRCs) to the scheme or other possible uses of free cash, as set out in the recovery plan section. These include:

- investment in the sustainable growth of the employer

- payments that result in covenant leakage

- discretionary payments to other creditors

- Trustees should also ‘add back’ contributions made to other DB schemes sponsored by the employer in order to assess cash flow but should recognise that contributions may need to be made to those other schemes.

- Trustees’ assessment of free cash flow should primarily be based on management forecast cash flow information.

- When reviewing the reasonableness of employer cash flow forecasts, trustees should be mindful of the employer’s position in its wider group, its interactions with other group companies (for example through transfer pricing, intergroup trading and/ or intergroup financing) and the impact this may have on free cash flows.

- Trustees should consider the appropriateness of management assumptions underpinning cash flow forecasts (relative to the risks and opportunities identified when assessing the employer’s market and overall prospects, as discussed below) and the sensitivity of these assumptions to future events, making appropriate adjustments where necessary.

- Where cash flow information is not produced for the employer (or it is not proportionate to produce for covenant assessment purposes), trustees should work with the employer to find a suitable proxy (for example EBITDA, profit before tax or consolidated cash flow), adjusted as necessary to best reflect the employer’s cash flow position.

- Where the employer’s cash flow is cyclical or subject to variance, trustees should consider using an average free cash flow over an appropriate period.

- Trustees may consider cash flows beyond the visible period. However, the reliability of cash support post visibility is determined as part of the trustee’s assessment of employer prospects.

Assessing an employer’s prospects

- The other factors likely to affect the performance or development of the employer(s) business that the trustees should consider are as follows:

- The employer's market outlook

- All material markets in which the employer operates, in terms of the relevant product/ service market and the geographical market.

- General market trends (for example whether it is a growing, stable or declining market, whether it is cyclical), the economic outlook for the countries that the employer or group operates in, and any potential risks to these markets.

- The employer's position within its market

- The employer's current market position, and the key strengths and weaknesses facing the employer and how these may impact the employer's market position in the future.

- The strategic importance of the employer within its group (if applicable)

- The employer’s position within the group and its interactions with other group companies.

- If the employer has strong operational or financial ties to the wider group, or the risks and opportunities associated with the wider group.

- The diversity of the employer’s operations

- The products and/ or services offered by the employer, the regions and markets they operate in, and the reliance or diversity of key customers and suppliers of the employer.

- Environmental, social and governance (ESG) factors

- ESG-related risks and opportunities facing the employer and how these may impact on the employer’s prospects.

- The resilience of the employer and the wider group (where applicable)

- The ability of the employer (and where applicable the group) to withstand market shocks or unanticipated events based on:

- the employer’s balance sheet, capital structure and other financial information

- the group’s financial resources to the extent that these are available to support the employer

- other non-financial indicators of resilience

- The ability of the employer (and where applicable the group) to withstand market shocks or unanticipated events based on:

- The risk of an employer insolvency event

- The employer’s insolvency risk and the potential outcome to the scheme in insolvency.

- The level of detail should be proportionate to the risk of insolvency, and the reliance placed by trustees on realising value from assets to fund the scheme and support risk.

- Any other relevant factors

- Other factors (including more general macroeconomic and geopolitical factors) that may be relevant to the circumstances of the employer’s business or market that may impact on the employer’s prospects.

- The employer's market outlook

- Trustees should consider how these factors might affect the reasonableness of the employer’s forecasts, and the employer’s profitability, free cash generation and balance sheet strength (including financing arrangements) beyond the visibility period.

- Together, these factors allow trustees to assess the employer’s prospects, and will in turn inform the trustees’ view on the maximum period in which trustees can reasonably assume that the employer will remain in existence to support the scheme, ie the employer’s covenant longevity.

- Where trustees are satisfied that covenant longevity extends to or beyond the scheme’s relevant date, the employer’s prospects are likely to be considered stronger. However, where covenant longevity is shorter than the period to the relevant date, prospects are more uncertain.

Contingent assets

- A contingent asset contributes to the strength of the covenant to the extent that:

- it is legally enforceable

- it will be sufficient to provide that level of support when required

- A contingent asset’s legal enforceability is determined by the terms and conditions of the relevant agreement and the applicable law. Trustees should consider obtaining legal advice in relation to the enforceability of proposed contingent assets.

- Common types of contingent asset are:

- guarantees from third parties, such as parent and group companies

- securities over cash, real estate and securities

- letters of credit and bank guarantees

- To understand whether a contingent asset will provide a particular level of support when required, trustees must identify the following:

- The scenario in which the contingent asset is likely (or able) to be called upon (for example in the event of insolvency of the employer).

- An appropriate method to assess the expected realisable value of the contingent asset. This will primarily be driven by the type of contingent asset, ie whether it is a security arrangement (for example security over an asset, cash in escrow, letter of credit) or a group or parental guarantee.

Valuing security arrangements

- Some assets have clear, demonstrable, readily recoverable value (for example cash in escrow or a letter of credit or surety bond provided by a recognised financial institutions), allowing trustees to recognise this value in full, subject to any limitations in the scheme’s legal access.

- Other assets have less certain value. For example, the value of security over a tangible asset such as a building or machinery will depend on the future market value for that asset and its condition at that time. Trustees must determine the most appropriate valuation methodology, considering the scenario and the timing in which any asset value is likely to be realised (for example insolvency) and their expectation of the development of the relevant market for that asset in the future.

- Where the contingent asset is provided by the employer (rather than a third-party), trustees must be mindful of the impact enforcing the security may have on the employer’s continued performance and financial ability to support the scheme. Where enforcement will have a material negative impact on the employer’s financial ability to support the scheme, trustees must also factor that cost into its valuation.

- Trustees should reassess the value of a security arrangement at each valuation as a minimum.

Valuing guarantees

- Some guarantees are structured in such a way that they largely replicate the obligations placed on a statutory employer. This includes providing a formal look through to the guarantor for affordability purposes. These guarantees provide an unfettered ability for trustees to claim against the guarantor in respect of all monies owed by the employer to the scheme and cannot be revoked without trustee agreement. These are referred to as 'look through' guarantees.

- Where trustees benefit from a look through guarantee, when assessing the strength of the employer covenant, trustees should assess the guarantor’s financial ability to support the scheme as if it was a statutory employer.

- However, if a guarantee doesn’t meet the criteria of a look through guarantee, trustees should determine the level of support a guarantee can provide by considering the following:

- The guaranteed amount (including whether the amount is capped and, where the amount is calculated by reference to the scheme’s funding position on a particular basis, how that funding position may develop over time).

- The circumstances in which a claim can be made under the guarantee (or, where the guarantee provides for a variety of triggers, the most likely scenario in which the guarantee would be called upon).

- The guarantor’s financial ability to provide that support at the time it may be required.

- Generally, we expect the level of reliance trustees place on a guarantee that can only be triggered by an unexpected future event such as employer insolvency to reduce with time, unless trustees can demonstrate with reasonable certainty what value would flow to the scheme.

Multi-employer schemes

- Schemes frequently have more than one employer. Trustees must consider the extent to which it is appropriate to analyse the financial ability of every sponsoring employer to support the scheme and how to reach an overall view on the covenant provided by the pool of employers as a whole.

- Where trustees determine it is not proportionate to review all employers, they should determine if alternative approaches are appropriate. For example, this could include pooling employers into sub-groups with varying levels of review for each.

- In considering which employers to assess in detail and the weight to be given to each, trustees should consider the following:

- The number of members of the scheme attributable to each employer, and an estimate of the size of each employer’s liability to the scheme. This should be based on an understanding of each employer’s share of the scheme’s liabilities, including orphan liabilities (ie those that are not attributable to any specific employer).

- The position of the scheme in the event of an insolvency or withdrawal of an employer, for example whether the scheme has segregation provisions and/or ‘last man standing’ arrangements.

- The trustees’ powers under the trust deed and rules to impose contributions.

- The likelihood of employer withdrawal and its impact and the treatment of any orphan liabilities.

- Any restrictions that might apply under the trust deed and rules to the allocation or payment of contributions due to the scheme, for example where member contribution rates constrain the level of overall contributions to the scheme.

Not-for-profit covenant assessments

- Not-for-profit organisations are organisations:

- where some (or all) of their activities are of a non-commercial nature

- that rely on donations (or other discretionary income or subscriptions) to fund their activities.

- Where not-for profit organisations have material commercial operations, these operations should be analysed in accordance with the general principles set out above in determining the strength of the employer covenant. The non-commercial operations of a not-for-profit should be assessed in accordance with the modifications below.

Assessing cash flow

- Where a not-for-profit organisation’s cash flow is generated largely from donations, when assessing the employer’s covenant visibility, reliability and longevity, trustees should recognise that the cash flow may be volatile and subject to reputational risk.

- Trustees should ascertain the extent and nature of any restrictions on the use of the employer’s cash flow (restricted funds) and consider the extent to which restricted funds are permitted to be used as contributions to the scheme.

- To the extent that an employer’s restricted funds are not permitted to be used as contributions to the scheme, those funds should be disregarded when assessing the financial ability of the employer to support the scheme.

Assessing prospects

- When assessing the outlook for the sector and the position of the employer within the sector, trustees should, in addition to considering the factors set out in section (C) above, specifically consider:

- the reputation and public profile of the employer and the impact of any changes to that on future donations

- the quality of governance of the organisation including its efficiency, management of reputational risks, and contingency plans for potential shocks to income (for example reputational damage), or demand for services

- the competition for income from other organisations

- the demand for the services it offers, including the impact of government policy and/or social factors (for example demographic assumptions) on potential revenue

- the macroeconomic environment

Contingent assets

- Where a contingent asset is provided by a not-for-profit organisation, trustees should consider whether the entity is subject to any restrictions that would prevent the trustees realising value in relation to the asset.

Chapter 7 - Journey planning

Introduction

- The second element of the funding and investment strategy is the trustees’ plan to bridge from the current funding position to the long-term funding target set in the funding and investment strategy (the 'journey plan').

- Trustees must decide the investment strategies they intend to adopt as the scheme moves towards the relevant date. The level of investment risk that corresponds to these investment strategies should be dependent on the strength of the employer covenant and, subject to that strength, the maturity of the scheme.

- The journey plan should reflect the circumstances of the scheme and the employer. The approach that trustees take when assessing the level of risk that can be supported over their journey plan should be proportionate to these circumstances. Trustees of schemes that have one or more of the following characteristics will more easily be able to conclude that the risks being run are supportable:

- The size of the employer is very large in comparison to the size of scheme.

- The scheme is already well-funded on a low dependency funding basis and/or solvency basis.

- The journey plan relies on only a small amount of funding and investment risk being taken in the period before their relevant date.

- Where those circumstances don’t apply, trustees will need to carry out a fuller assessment of the covenant and a more detailed analysis of the level of risk to allow for in the journey plan. Further details of how to assess the covenant are provided in ‘detail of the journey plan’.

Detail of the journey plan

- The journey plan forms part of the funding and investment strategy. It will therefore be reviewed (and, where appropriate, revised) whenever the funding and investment strategy as a whole is reviewed.

- The funding and investment strategy is subject to employer agreement.

- Trustees should determine their plan to transition from the scheme’s existing investment portfolio to one that would meet the standards of a low dependency investment allocation. Trustees should also plan for how the scheme will reach a position of being at least 100% funded on a low dependency funding basis on and after the relevant date[2].

- This plan should set out:

- the date at which they intend the scheme’s investments to meet the standards of a low dependency investment allocation (which may be the scheme’s relevant date, or before that date);

- the shape of their de-risking strategy; and

- a qualitative description of the intended future approach to the actuarial assumptions for the technical provisions over time as the scheme moves from its current funding position to the relevant date.

- When determining this plan, trustees must take into account the principle that the level of risk should be:

- dependent on the strength of the employer covenant (so that more risk can be allowed for where the employer covenant is stronger, and less risk can be taken where the employer covenant is weaker)

- subject to the above, dependent on how near the scheme is to reaching the relevant date (so that, subject to the strength of the employer covenant, more risk can be allowed for where a scheme is a long way from reaching the relevant date and less risk can be allowed for where a scheme is near to reaching the relevant date)

- Granular detail relevant to the journey plan must be recorded in Part 2 of the statement of strategy. These details do not form part of the funding and investment strategy and are subject to the requirement to consult with the employer, rather than reach agreement.

- The details of the journey plan to be recorded in Part 2 of the statement of strategy include:

- the current level of risk in relation to the investment of the assets of the scheme

- the level of risk the trustees intend to take in relation to the investment of the assets of the scheme as it moves along its journey plan

- the proportion of assets intended to be allocated to different categories of investments as the scheme moves along its journey plan

- the discount rate or rates and other assumptions used in calculating the scheme's TPs in the actuarial valuation to which the funding and investment strategy relates, and how the trustees expect the discount rate(s) to change over time

Supportable risk

- When considering the level of risk that is appropriate for the journey plan, trustees should consider separately the following two periods of time:

- The period during covenant reliability; and

- The period after covenant reliability and up to the relevant date.

- The following sections ('Journey planning – period of covenant reliability' and 'Journey planning – Period after covenant reliability') set out our general expectations for how trustees should approach these two periods of time for their journey plan.

Maturity

- The supportability principles set out that, subject to the strength of the employer covenant, more risk can be taken where a scheme is further from the date of significant maturity.

- In deciding on the appropriate level of risk, more immature schemes will be able to justify holding risk for longer. This additional period of risk-taking can be reflected in the de-risking journey plan of more immature schemes. Trustees should ensure that this is still set in the context of the strength of the employer covenant.

Journey planning – period of covenant reliability

- During this period, trustees should consider both the likelihood and monetary impact of risks crystalising and the ability of the employer or any contingent assets to repair any deficit.

- We expect trustees to analyse these aspects in reaching any conclusion about how they have satisfied themselves that the risks inherent in the de-risking journey are supportable by the strength of the employer covenant.

- To assess the investment risk and the impact this would have on funding, schemes should carry out scenario analysis of alternative economic conditions to determine the estimated impact on the scheme’s asset and liability values, as well as that of the employer covenant. The level of complexity within that scenario analysis should be proportionate to their scheme and employer’s position.

- This analysis should be compared to the trustees’ assessment of the strength of the covenant.

- All trustees should carry out some form of stochastic or deterministic analysis to help them understand plausible outcomes from risk events. Trustees should identify the actions they intend to take in the event of a stress scenario to repair any deficit.

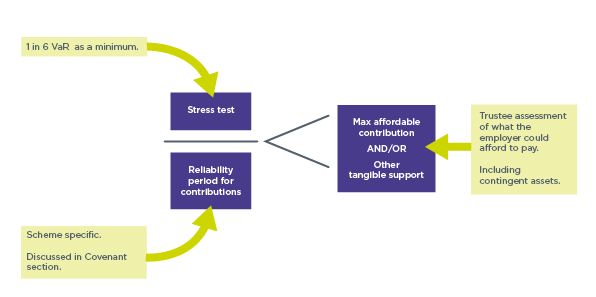

- We would expect that a scheme considers an asset and liability Value at Risk (VaR) of at least 1-in-6 downside level event and the ability of the employer to repair any additional deficit from that event.

- Trustees should be confident that the employer covenant can support the impact of this downside analysis and additional risk from the recovery plan.

- If trustees are relying on the employer to make future payments to the scheme to mitigate these risks, then the trustees should assess the employer’s available cash after deducting DRCs to the scheme and other DB schemes the employer sponsors.

- The level of affordability from that assessment should only be assumed over the period of reliability, as described in the above section.

- If trustees are relying on a contingent asset or other form of tangible support that will provide additional funding to the scheme, then they should ensure it satisfies the relevant criteria set out above.

- This will allow the trustees to understand whether the employer has sufficient affordability over the period of reliability to remedy any deficit from the downside scenario.

- This approach can be used to determine the maximum risk (known as the maximum risk test) trustees should assume will be run during the period covered in the journey plan, ie test the largest deficit increase the employer could afford to remedy in line with the above approach. In practice, trustees may prefer to assume a lower level of risk.

- This approach is illustrated in the below graphic

- We expect trustees to determine a de-risking journey which is consistent with these parameters (or such other parameters as the trustees adopt) during the period of covenant reliability.

- If the end of the period of covenant reliability is after the relevant date, then the journey plan must reflect that the scheme will be assumed to adopt the low dependency investment allocation at the relevant date.

Calculating the stress test

- Trustees should use, as a minimum, the TPs as the basis for the liabilities for the purposes of this test and not adjust the expected return assumptions post stress. The rationale for the assumptions used and model description for calculating VaR should be documented.

- For small schemes, using our stress test as set out in Fast Track as a proxy for a 1-in-6, 1-year downside scenario would be an acceptable approach.

- Trustees should include any allowance for investment outperformance being made in any existing recovery plan as part of this stress test. To do this, trustees should calculate the outstanding TPs deficit after only giving credit for the monetary net present value of the cash contributions promised in the future (net present value calculated using the assumptions consistent with those used to calculate the TPs).

Journey planning – Period after covenant reliability

- After the period of covenant reliability, trustees will need to consider what level of risk is appropriate and to what extent they need to allow for the scheme to de-risk before the relevant date.

- These considerations will depend on the level of risk being taken in the period of covenant reliability and include the timing and pace of any de-risking planned to be undertaken in the investment strategy.

- When considering the appropriate level during this period, the trustees should consider the impact of adverse changes and the likely actions they can take to mitigate them. This will depend on the level of risk in the investment strategy and to what extent this is reflected in the TPs.

- This analysis of risk should also consider the extent to which the covenant is likely to be able to support risk in the future. This does not mean that we expect risk can only be taken where it is possible to forecast covenant with reasonable certainty. However, the trustees should understand the impact of a future deterioration in covenant.

- Where adverse changes in covenant are likely in future, we would expect the trustees to allow for those.

Investment de-risking considerations

- If a scheme’s existing portfolio means that a de-risking plan is required, trustees should consider the type of assets they plan to disinvest from and those they plan to invest in. Actions associated with de-risking may include:

- reducing the level of risk associated with the growth assets

- decreasing the overall percentage of assets held in growth assets

- increasing the level of matching assets and reviewing the level of duration and inflation matching between the assets and liabilities

- increasing the cashflow matching more generally

- These plans should reflect a converging of the investment strategy to the principles of the low dependency investment allocation.

Choice of de-risking strategies

- If a de-risking plan is required, trustees should plan a de-risking approach that suits their scheme-specific characteristics bearing in mind the principles discussed in this section. Common de-risking strategies include the following:

Linear de-risking

- The assumed level of investment risk and return reduces progressively over time as the scheme matures. The rate of progression is linear, creating a smooth path towards low dependency.

Horizon (or ‘lower for longer’) approach

- Under this approach, there is one level of assumed investment risk and return in the period before the scheme reaches the relevant date and a lower level of assumed investment risk consistent with low dependency funding thereafter. Typically, this entails the scheme taking a lower level of risk than under the linear approach but maintaining the same level of risk over a longer period.

Stepped de-risking

- The time before the scheme reaches its long-term objective is split into a number of periods with a constant level of investment risk, which reduces as the scheme transitions from one period to the next.

- Other strategies might be a combination of the above. This is not an exhaustive list and further strategies, for example de-risking based on funding level are also possible. Other strategies might be a combination of these. There are many different combinations and, providing the principles outlined here are adhered to, all are potentially acceptable.

The journey plan and choice of relevant date

- In determining their journey plan, the trustees should bear in mind that the choice of relevant date will affect the risk inherent in the journey plan.

- For example, where trustees choose a relevant date well in advance of the date of significant maturity, they will have flexibility to push back the relevant date in the event of adverse experience. The trustees will then have longer to reach full funding and the risk of not being fully funded by the time of significant maturity is reduced.

Journey planning for open schemes

- For the purposes of journey planning, open schemes can assume an allowance for future accrual and new entrants, which will delay the time the scheme reaches significant maturity.

- This means we would expect that open schemes can allow for taking investment risk over a longer period of time than an equivalent closed scheme with an equivalent employer.

- We expect any allowance for new entrants and/or future accrual to be reasonable. We discuss this issue further and our expectation of what reasonable means in this context in the TPs section.

Other considerations

- Trustees should ensure that that their de-risking plan will be practicable. For example we would expect the trustees to consider the following:

- Their investment governance model and whether it can support the planned de-risking strategy, for example the frequency of reviews and changes to asset allocations incorporated in their plan.

- The timeframes for significant de-risking. We would not expect the trustees to assume significant de-risking to occur instantaneously or over a short time period where in practice they would expect this to take longer to minimise risk. This is especially true of any de-risking that is assumed to occur at significant maturity. Specific consideration should be given to allowing sufficient time for illiquid investments to be disinvested in the journey plan.

- The duration-based measure for significant maturity. As the requirement is for a scheme’s relevant date to be assessed using duration, we would expect the journey to reflect this measure in a proportionate way. Therefore, we expect that de-risking in the journey plan should be measured, to some extent, against duration.

- Many trustees currently choose to have de-risking 'triggers' which are engaged when a scheme reaches a particular funding level. These strategies can remain in place, however we expect them to be in addition to the de-risking triggered by reference to change in duration. The journey plan should therefore, as a minimum, plan for de-risking no later than the relevant date regardless of the scheme’s expected funding level. In practice, we expect most journey plans to plan extensive de-risking in advance of the relevant date.

- There is one exception to the duration-based principle referenced above. We would expect covenant reviews to occur at least in line with the schemes valuation. Where the period of covenant reliability is more than three years, it would be reasonable to assume no change in investment strategy during the three-year period between valuations, regardless of changes in duration. However, if the trustees become aware of a material deterioration in covenant during this short timeframe, it should prompt a more urgent review of the funding and investment strategy.

- At a future valuation, even if the assessment of covenant does not change (for example the period of covenant reliability remains constant), for closed schemes this means the end point of covenant reliability will be closer to the relevant date. This assumes the relevant date has not changed because of changes to market conditions and/or the scheme membership. Therefore, it might be reasonable for the trustees to conclude at a review that it is appropriate to take more risk in its journey plan in future by extending the period before de-risking even if their assessment of covenant is unchanged.

Our expectations of the maximum risk strategy that can be taken

- The principles below outline the maximum level of risk we believe is appropriate in deciding on a journey plan. We expect many schemes will choose to adopt a journey plan with less risk since employers may want to limit volatility in the journey plan and/or the trustees consider that a lower risk approach is more appropriate.

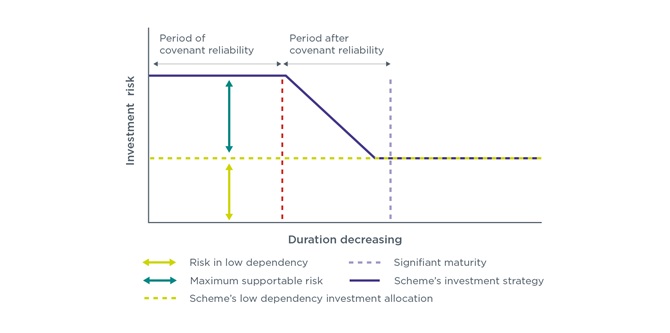

- If trustees are taking this maximum level of risk, our expectation is that the trustees will assume that the level of investment risk will reduce by at least linear de-risking, measured over the period starting with the end of covenant reliability and finishing at significant maturity.

- This would reduce the level of risk assumed in the journey plan from the level considered to be the maximum supportable by the employer covenant, to that derived from the low dependency investment allocation.

- This approach is represented in the diagram below:

- This linear approach may not be appropriate where, for example, trustees have concerns about the longevity of the employer covenant, particularly where the period of covenant longevity ends before relevant date. In these circumstances, trustees should consider whether a more rapid de-risking should be assumed in the journey plan.

- The trustees do not have to assume that investment risk will reduce by linear de-risking. However, in determining the level of risk that is appropriate in a maximum risk strategy, we would not normally expect this to be greater than assuming linear de-risking.

- These principles set out our general expectation for the maximum risk strategy the trustees might take. If the scheme assumes less risk than that determined under the maximum risk test during the period of covenant reliability, then the trustees may wish, for example, to plan to hold that lower level of risk for longer (horizon method) or have a slower de-risking path.

- Overall, broadly, we would not normally expect the overall risk assumed in the journey plan to be greater than that assuming maximum risk at the start and then linear de-risking after the reliability period has ended. We would expect any analysis required to check this level of risk to be proportionate to the circumstances of the scheme and the level of risk taken.

- The approach described above means that, for schemes with identical employers, a more immature scheme will have a slower pace of planned de-risking than a more mature scheme. In this way, more immature schemes can be assumed to be able to take more risk than a mature scheme.

Chapter 8 - Statement of strategy

Introduction

- Trustees must prepare a written statement of strategy made up of two parts:

- Part 1, which records the funding and investment strategy.

- Part 2, which records various supplementary matters, including various details in relation to the journey plan, how well the funding and investment strategy is being implemented, the main risks to the strategy and how they are being managed.

- This statement must be prepared as soon as reasonably practicable following a determination or revision of the scheme’s funding and investment strategy.

- The statement of strategy must be submitted to us with every valuation submission or revised valuation.

- The statement of strategy must be signed on behalf of the trustees by the chair of trustees. If the scheme does not have a chair, the trustees must appoint one. A chair must be:

- an individual who is a trustee of the scheme

- a professional trustee body which is the trustee of the scheme

- where a company which is not a professional trustee body is a trustee of the scheme, an individual who is a director of the scheme or a professional trustee body which is a director of that company, or

- for a scheme established under section 67 of the Pensions Act 2008, a member of the trustee corporation

Funding and investment strategy

- Trustees will have to set out how they will achieve low dependency on their sponsoring employer by the time they expect to reach their relevant date. They must provide information on the scheme’s assets they intend to hold at the relevant date in line with a low dependency investment allocation. They must explain how they expect to be at least fully funded on a low dependency funding basis by their relevant date.

- Within the statement of strategy, the trustees must explain how well the funding and investment strategy is being successfully implemented, reflecting on past actions and lessons learned, as well as any remedial action they plan to take to rectify divergence from the intended course.

Key themes in the Funding and Investment Strategy

- Trustees must record their funding and investment strategy in the statement of strategy in a number of key areas including the following: